CHRO relevance is on the line

Just 7% of CEOs see CHROs as AI-savvy. To stay relevant, HR leaders must lead human-AI work design.

.webp)

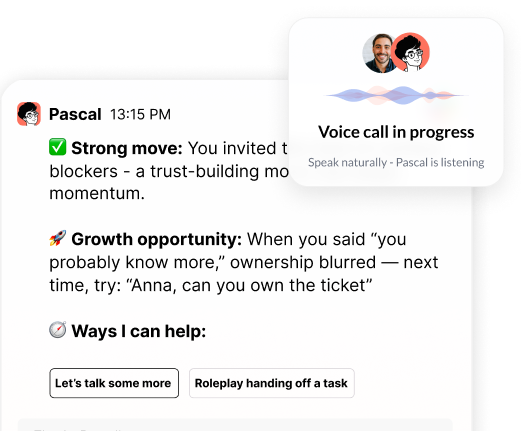

“Thank you for setting the great foundation for my promotion; now I have a plan!"

Curious to see how AI Coaching can 10X the impact and scale of your development initiatives. Book a demo today for:

The gap between AI's promise and its performance in the workplace keeps widening. MIT research shows that 95% of AI projects fail to deliver expected results. That number should make every people leader pause.

Gail Fierstein has spent her career at the intersection of technology and human capability. She's led transformations most recently as Chief People Officer at CaaStle. Earlier, at Goldman Sachs and Pearson, Gail worked with C-Suite execs and led organizational change and talent development, and now guides multiple HR tech startups through adoption challenges. Her background as a software engineer turned HR executive gives her a rare dual lens on what actually drives change.

Her perspective on why AI initiatives stumble cuts through the usual explanations. The challenge isn't technical. The challenge is happening in the last mile of implementation.

Gail points to Gartner's hype cycle to explain where we are with AI. After the innovation trigger comes the peak of inflated expectations. "You can't have a conversation personally or professionally without talking about AI," she notes. Every success story comes with two or three quiet failures that never launch or gain traction.

As Gail observes, "There are signs that AI is headed into the Trough of Disillusionment stage." A Fortune article states that 95% of AI projects are failing primarily due to a "learning gap" on the best way to use AI tools and understand the impact on roles and the organization.

The pattern repeats itself across technology transformations. Leaders invest in tools, announce rollouts, and expect behavior change to follow. What gets skipped is change management. "No one likes to do that last mile," Gail explains. "It's hard."

Her early career experience as a software engineer taught her this lesson directly. She was automating manual trading operations, sitting with the team, learning their workflows, designing new systems. The work was going well until she walked into a bar one evening. "The Terminator is here," someone called out. The comment landed hard. "I was devastated," she recalls.

That moment forced a shift in approach. She had to figure out how to bring people along in the process, help them contribute ideas, and identify who would succeed in the new environment versus who would struggle. The real insight came later. "People think technology is eliminating their jobs, but it's not that," Gail says. "It's people who could adapt and know how to use the system most effectively will eliminate their jobs."

Past technology transformations focused on process improvement, replacing old systems with new ones, or fundamentally changing consumer behavior. Those changes required new skills, mostly in engineering, or new ways of working.

AI operates differently. "AI questions what humans still need to do," Gail explains. The implication reaches beyond learning new software or updating workflows. Organizations need to identify the sustainable skills that help humans adapt in an AI-enabled environment.

Critical thinking and problem solving top the list. These capabilities become necessary both for working alongside AI and for handling the tasks that AI cannot. MIT research on 20,000 tasks across 1,000 jobs identified five core segments where humans maintain unique advantage: empathy and trust-building, tasks requiring physical presence, ethical judgment, creativity, and what researchers call hope, which means aligning people toward a future worth pursuing.

For HR leaders, this moment creates an opening. "There's been an age-old struggle between HR leaders and executives on emphasizing these skills," Gail points out. Companies have historically prioritized technical skills that fill seats quickly. Broader capabilities like systems thinking or creative problem solving got secondary treatment despite HR advocacy. AI forces that conversation forward.

Gail's recommendation breaks from traditional HR structure. Rather than creating separate AI transformation roles or bolting on new titles, she suggests modeling HR after product organizations.

"Just like when years ago there was a debate, do you have your diversity teams separate from your HR teams? My philosophy has always been no because you're just going to have double effort and shadow orgs," she explains. The same logic applies to AI adoption.

Product teams focus on experience rather than just process. They work iteratively, test assumptions, and adapt based on usage patterns. They rarely operate in silos. A product person doesn't work alone, they collaborate with engineers, designers, and business stakeholders as part of product management or product development capability. HR teams can adopt this same mindset.

"Maybe it now becomes people product," Gail suggests. That shift means focusing on employee experience as the primary outcome, using agile frameworks to iterate on programs, and applying product tools like journey maps and personas to understand how people actually work.

The framework also changes how HR measures success. Product teams constantly look for product-market fit and evolve based on real-world usage. HR can do the same with talent programs and AI adoption initiatives.

The famous nine-box for performance and potential still has value, but its definitions need updating. "What companies and HR need to do is define what is performance and potential in the context of the human-AI collaborative," Gail explains. "It's different."

That difference requires building AI adoption criteria directly into performance frameworks. How someone uses AI tools matters as much as what they deliver. Companies like Zapier have started doing this, creating performance standards that explicitly measure AI-native adoption and building those expectations into rating systems.

The approach removes the optionality that kills most initiatives. When AI proficiency becomes part of how performance gets evaluated, adoption stops being a nice-to-have. It becomes required.

But mandates alone don't work. Gail emphasizes the need for real incentives. At Goldman Sachs, when building out the Bangalore office required teams to rethink their structure and processes, the firm offered a two-to-one or three-to-one headcount ratio for the teams leveraging the new location.. "It was very effective because the incentive was real and forced people to think differently."

For AI adoption, the incentive structure needs similar clarity. What do employees get from changing how they work? Research on legal offices testing AI tools found that framing matters. One office was told to use AI to become more productive. Another office was told to use it to eliminate tasks they didn't want to do. The latter group showed significantly higher adoption rates.

"At the end of the day employees are like, what's in it for me?" Gail notes. Eliminating unwanted work provides a clear answer.

About 18 months into the current AI wave, Gail ran a hackathon with her people team. The goal was simple: take away the fear that was freezing decision-making. "We invited IT to participate in the readouts of the ideas that came up because we didn't even have an enterprise product yet," she recalls.

The hackathon produced multiple outcomes. Teams surfaced ideas for eliminating tedious tasks, improving onboarding experiences, and using AI to enhance employee support. More importantly, it opened minds and built confidence. The event also made clear that the company needed to select an enterprise AI product for broader use.

Innovation got rewarded through recognition tied to cultural values. When giving feedback to employees, managers cited contributions from the hackathon because innovation mattered to how the company defined success.

The hackathon approach works because it reframes AI from threat to opportunity. People get agency in the process. They experiment in a low-stakes environment. They see practical applications rather than abstract possibilities. Fear diminishes through exposure and play.

CHROs typically align closely with CFOs because budget approval flows through finance. That partnership matters and should continue. But Gail sees a more powerful coalition emerging.

"I think the trifecta is the CHRO, the chief product officer, and your CTO," she explains. "Those three functions working together can reshape how an organization operates, not just around AI but across any significant change."

The logic is straightforward. The CTO understands technical capabilities and constraints. The chief product officer thinks in terms of user experience, iteration, and business outcomes. The CHRO knows people, culture, and how to build capability at scale.

When those three perspectives combine, the organization gets both the technical foundation and the human enablement required for successful transformation. "CHROs should think about who they're working with, what opportunities they could have to work with the chief product officer or their CTO," Gail advises. "Build that future together."

If HR teams get this right, several things happen.

First, the role itself expands. Success gives CHROs optionality to broaden their remit into business strategy, revenue generation, or even P&L responsibility. When teams include both digital and human teammates, HR's ability to manage that complexity becomes a competitive advantage.

Second, career paths into HR diversify. Gail's trajectory from software engineer to HR executive was unusual. In the future, product managers, engineers, and other technical roles may flow into people leadership more naturally. That crossover strengthens the function.

Third, organizations build real capability to navigate ongoing change. AI represents one transformation in a continuous series. Teams that learn to adopt new tools quickly, measure what matters, and support people through transitions gain durable advantage.

The current moment requires people leaders to step forward. AI's arrival creates urgency, but the underlying challenge of driving adoption and building adaptive capability isn't new. What's changed is that the technology itself makes the case for focusing on human skills, collaboration, and experience.

HR has been advocating for these priorities for decades. Now the conversation has shifted in their favor.

.png)